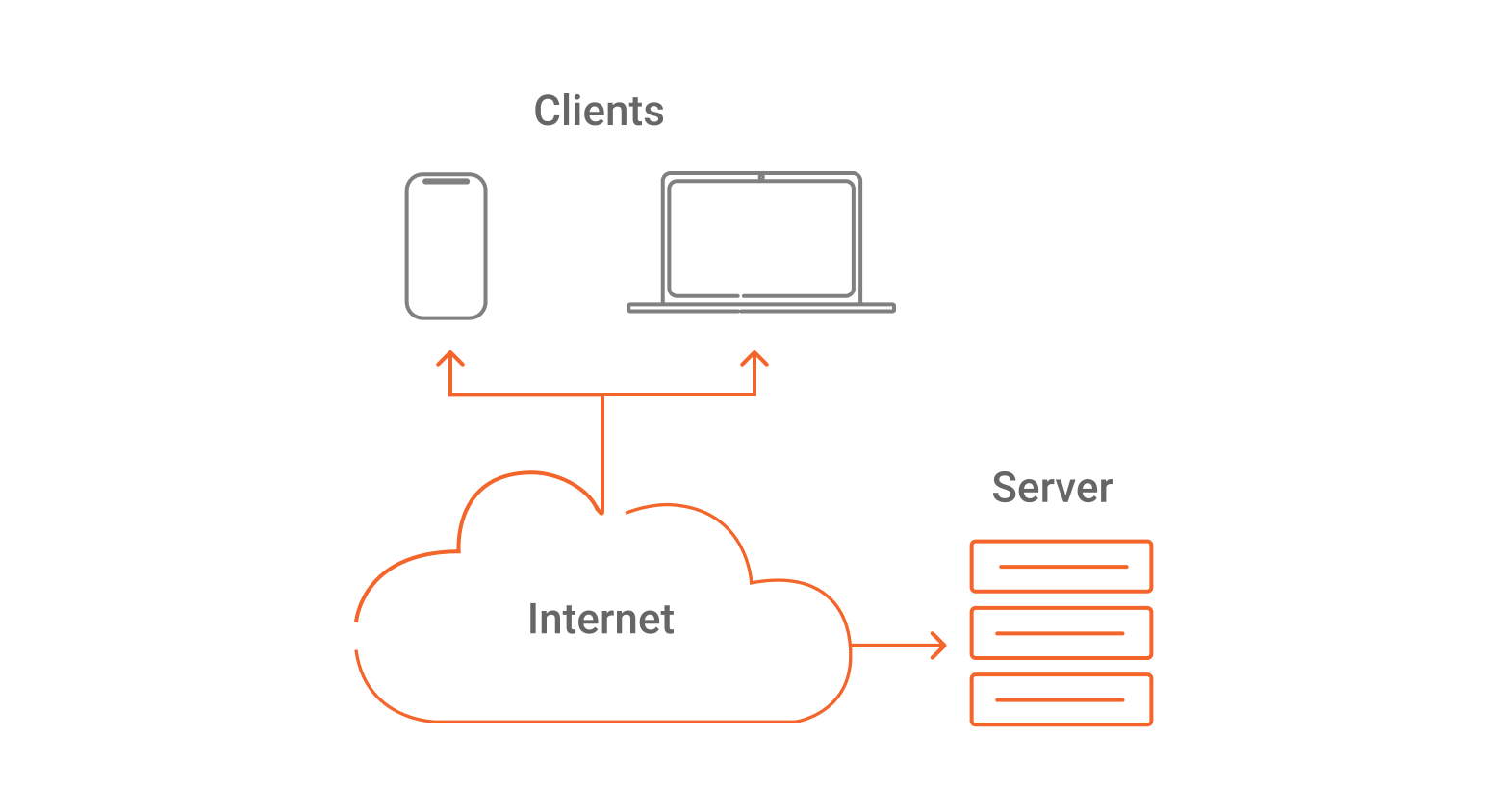

HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) is a stateless request–response protocol used by clients and servers to exchange resources such as HTML pages, JSON API responses, images, and files. It runs at the application layer (Layer 7) and typically uses TCP (HTTP/1.1, HTTP/2) or QUIC over UDP (HTTP/3) as its transport.

In other words,If you don’t remember or haven’t noticed, it appears at the beginning of a website address. HTTP is a text-based application layer transfer protocol and is considered the basis for data communication between networked devices. During this request-response process, HTTP uses pre-defined standards and rules for the exchange of information. In general, HTTP is the protocol that clients and servers use to communicate.

In addition, for data exchange to take place, HTTP depends on two other network protocols: TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) and IP (Internet Protocol). From this, we have the TCP/IP model, which is part of the communication process between clients and servers and also between servers and Mobile/Web APIs. HTTP is the most used protocol for web-based applications and APIs.

Note that TCP/IP is a model, but also a protocol stack that HTTP falls into. Regarding the OSI model – which we’ll talk about later – TCP is layer 4 and IP is layer 3.

When to use HTTP (and HTTPS)

- When building websites and web apps accessed by browsers.

- When exposing or consuming APIs (REST/JSON, GraphQL over HTTP).

- When you need standard methods (GET/POST/PUT/PATCH/DELETE) and status codes to model operations.

- When you want caching, content negotiation, and proxy/CDN compatibility.

- When integrating with common internet infrastructure (load balancers, gateways, CDNs, WAFs).

In practice, use HTTPS for nearly all public traffic (HTTP encrypted with TLS).

When not to use HTTP

- When you need real-time bidirectional messaging with minimal overhead (consider WebSocket or gRPC streaming).

- When the workload is low-latency machine-to-machine with strict contracts and binary protocols (consider gRPC).

- When the network is constrained and you need pub/sub semantics (consider MQTT).

- When you need file transfer semantics with specialized features (consider SFTP/FTPS depending on requirements).

- When using HTTP would force unnatural modeling (e.g., high-frequency telemetry without batching).

Signals you need to understand HTTP (symptoms)

- Users report “site is slow” but backend CPU looks fine.

- You see many 4xx/5xx errors and don’t know whether they’re client-side or server-side issues.

- CORS problems: browser errors like “blocked by CORS policy”.

- Caching doesn’t work: assets are re-downloaded; cache hit ratio is low.

- Sessions “randomly” break due to misunderstanding statelessness, cookies, or headers.

- You can’t explain why HTTP/2 helps but head-of-line blocking still happens on some networks.

How HTTP works (decision-ready mental model)

1) URL → where and how to connect

A URL tells the client:

- Scheme:

http://orhttps://(rules + security expectations) - Host:

example.com(where to connect) - Path:

/products/123(which resource) - Optional: query

?page=2, fragment#faq

2) Client opens a connection

- HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2 typically use TCP.

- HTTP/3 uses QUIC, which runs over UDP.

3) Client sends an HTTP request

A request contains:

- Method (GET, POST, PUT, PATCH, DELETE, etc.)

- Path/URI

- Headers (metadata like

Host,Accept,Authorization) - Optional body (common in POST/PUT/PATCH)

4) Server returns an HTTP response

A response contains:

- Status code (e.g., 200, 301, 401, 404, 500)

- Headers (e.g.,

Content-Type,Cache-Control) - Optional body (HTML, JSON, image bytes, etc.)

5) Caches and intermediaries can participate

CDNs, proxies, and browsers may store responses and reuse them based on HTTP caching rules.

Stateless Nature

HTTP is stateless at the application level: each request is processed independently, and the server is not required to remember prior requests.

State is usually added via cookies, tokens, or server-side sessions referenced by identifiers.

That is, even if several requests are made at the same time, one doesn’t know that the other exists, and the server doesn’t store any information about the client’s state. As soon as a TCP connection is made, all information exchanged is lost. The advantages of this are that there is a reduction in the memory usage on the server and a reduction in the problems resulting from an expired session.

It’s also important to mention that HTTP is stateless if viewed from a high level of abstraction, but it’s also based on TCP (not UDP), and thus is connection-based and stateful from a lower-layer standpoint. What this means is that because it’s connection-based, it’s stateful in delivery, which ensures that all packets are received and sequenced correctly.

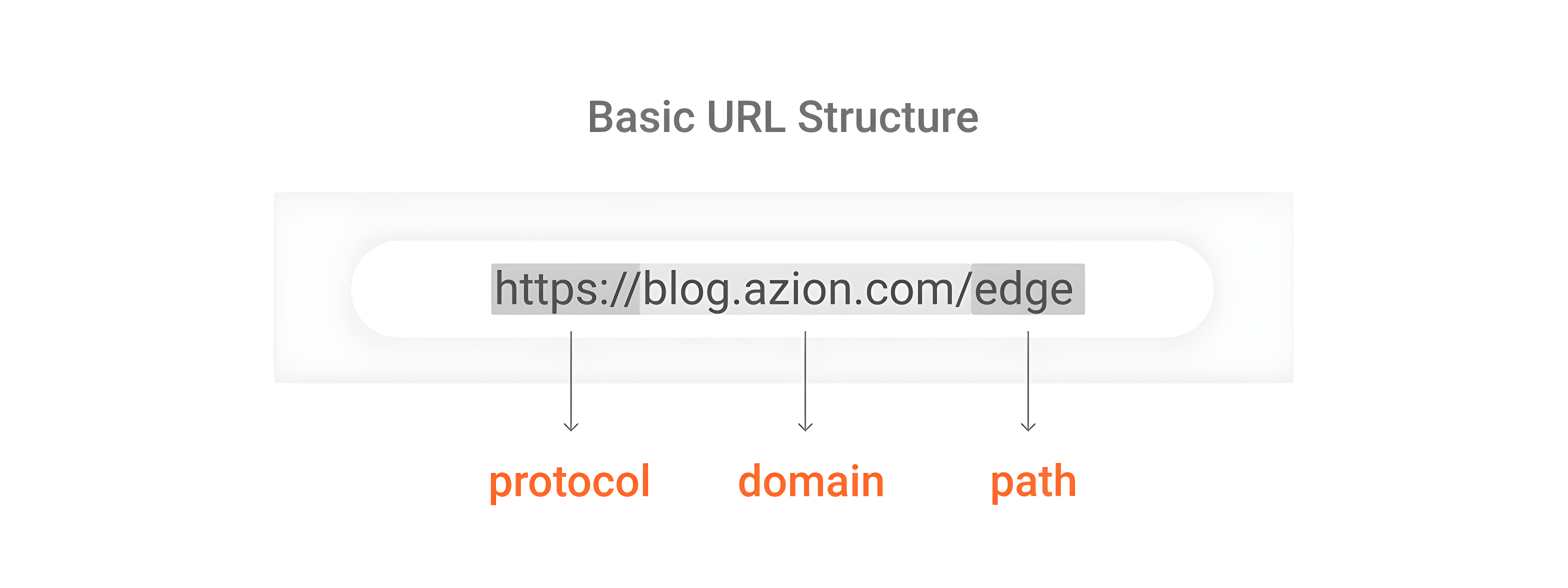

URL

We already know what a URL is, and that it’s the first step in the information exchange process. But, although it’s part of our everyday online life, many of us don’t know what its structure means. So, let’s consider the following URL:

In its basic form, we can divide the URL into three parts:

- The protocol (http:// or https://) - tells your browser how to communicate with a website’s server to send and retrieve information. When it’s HTTPS, it’s a secure HTTP that has some additional security standards and encrypted text.

- The domain (azion.com) - has the subdomain (blog.), the name by which the website is known (azion), and the TLD (.com). TLD stands for Top Level Domain, which is the category of the websites such as .com (commercial), .org (organizations), and .net (networks).

- The path (/edge) - directs the browser to a specific page on the website.

History of HTTP

Let’s begin with the term hypertext, which was created by Ted Nelson in 1965 and was defined as “non-sequential writing.” In other words, it’s a type of text that branches, it isn’t necessarily linear and contains links to other texts. This term, in turn, was inspired by the ideas of Vannevar Bush previously presented in his 1945 paper As We May Think.

Later, in 1989, Tim Berners-Lee proposed the WorldWideWeb project and, in 1991, he and his team created a protocol that would allow the retrieval of texts from other documents via hypertext links, which would become the original HTTP format. Hypertexts were the first files that used HTML (HyperText Mark-up Language), a textual format to represent documents in hypertext. HTML as well as hypertext is text, but it can serve as commands, including calling on other assets like images, videos, audios, etc. Its latest version is the HTML5.

Like everything else in the Internet world, the HTTP protocol has undergone several transformations and has evolved a lot, as can be seen below.

- HTTP/0.9 - The first version was launched in 1991 and was very simple. It focused on text transfer and only had the GET request method; it had no HTTP headers, status or error codes.

- HTTP/1.0 - This later version is from 1996, and presented, in addition to simple text transfer, the transmission of more sophisticated data, such as request/response metadata and content negotiation.

- HTTP/1.1 - This version from 1999 is considered a milestone in the evolution of the Internet, since it eliminated several problems from previous versions and introduced a series of optimizations, such as an additional cache mechanism, fragmented encoding transfers, request pipelining and encryption of transfer. Although there is a more recent version, this is still the standard and most used version in the world.

- HTTP/2 - This version is from 2015 and is better prepared for today’s massive and widespread Internet use. Although there has been no change in semantics from the previous version, some notable benefits are better performance in transporting information and data security and significantly lower latency.

- HTTP/3 - Launched in 2019, the HTTP/3 protocol is even faster, more reliable and more secure. It presents a fundamental difference from the previous version: a new transport protocol, the QUIC. QUIC is based on UDP (User Datagram Protocol), which is faster than TCP in transmitting data, as it doesn’t go through the data verification process; this, however, makes it less secure. Although it isn’t a reliable transport, QUIC adds an extra layer to UDP, bringing features like packet retransmission and congestion control. Another important feature of HTTP/3 is that it supports HTML5, the most modern version of HTML, which adds the ability to do native programming.

HTTP versions (what changes, what doesn’t)

Version | Transport | Key change | Typical impact |

HTTP/1.1 | TCP | Persistent connections, better caching rules | Widely compatible; can suffer from head-of-line blocking per connection |

HTTP/2 | TCP | Multiplexing, header compression | Better page load under concurrency; still TCP head-of-line at transport level |

HTTP/3 | QUIC over UDP | Transport redesign + faster handshakes | Better performance on lossy networks; reduces some latency issues |

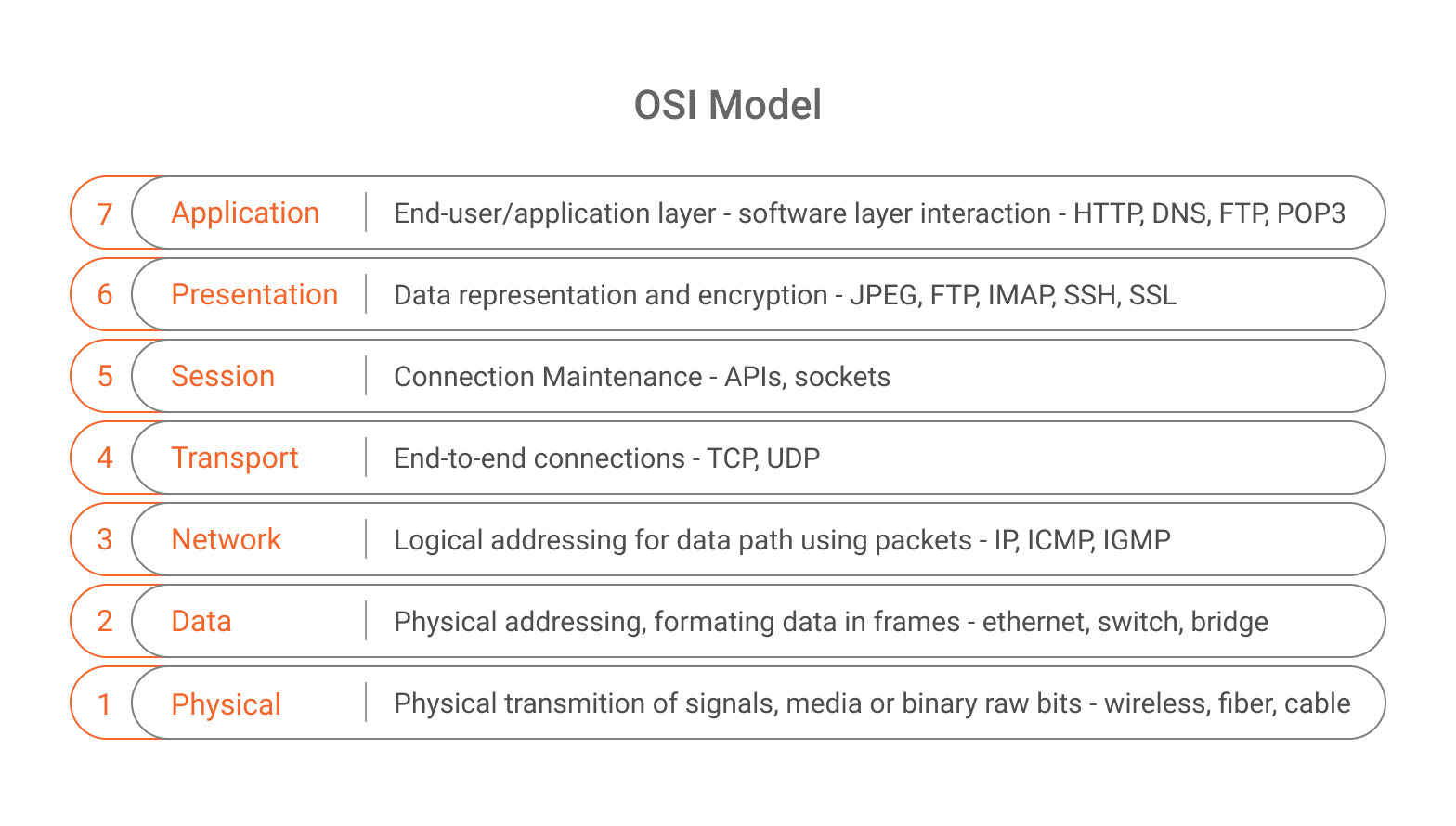

Understanding Where HTTP Fits in the Communication Puzzle

HTTP is a small piece in the communication stack, but how does it fit into it? To better understand it, let’s first have a quick view of the OSI model first.

The OSI (Open System Interconnection) model, created by the International Organization for Standardization in 1971, is a model of computer networks that serves as a standard, or rules, for communication protocols between different systems on a network. That is, it’s as if it were a universal language for computer networks. In this model, the communication system is divided into seven abstract layers, each one with a specific functionality.

The HTTP protocol acts precisely at layer 7, the application layer, where the interaction between users and computers happens – when users visit a website or check e-mails, for example. The application layer is responsible for the protocols and data manipulation on which the software depends to present meaningful data to the user. In addition to HTTP, other protocols that operate at the application layer are: HTTPS, DNS, FTP, IMAP, MIME, POP, RTP, SMTP, TELNET, TFTP and TLS.

The HTTP Communication

When a client wants to communicate with a server, the first thing that happens, after the user types the URL in the browser address bar or goes to another page, is opening a TCP/IP connection, and the HTTP request is sent to the server. In that request, there is a message with a series of data describing what the customer has requested. The server then sends the response to the client, which also contains data that can be read. Finally, the request-response process is finalized. Keep in mind that everything here usually takes microseconds to happen.

In the communication process we described above, you might have noticed that there are two essential agents: the request and the response.

HTTP Messages

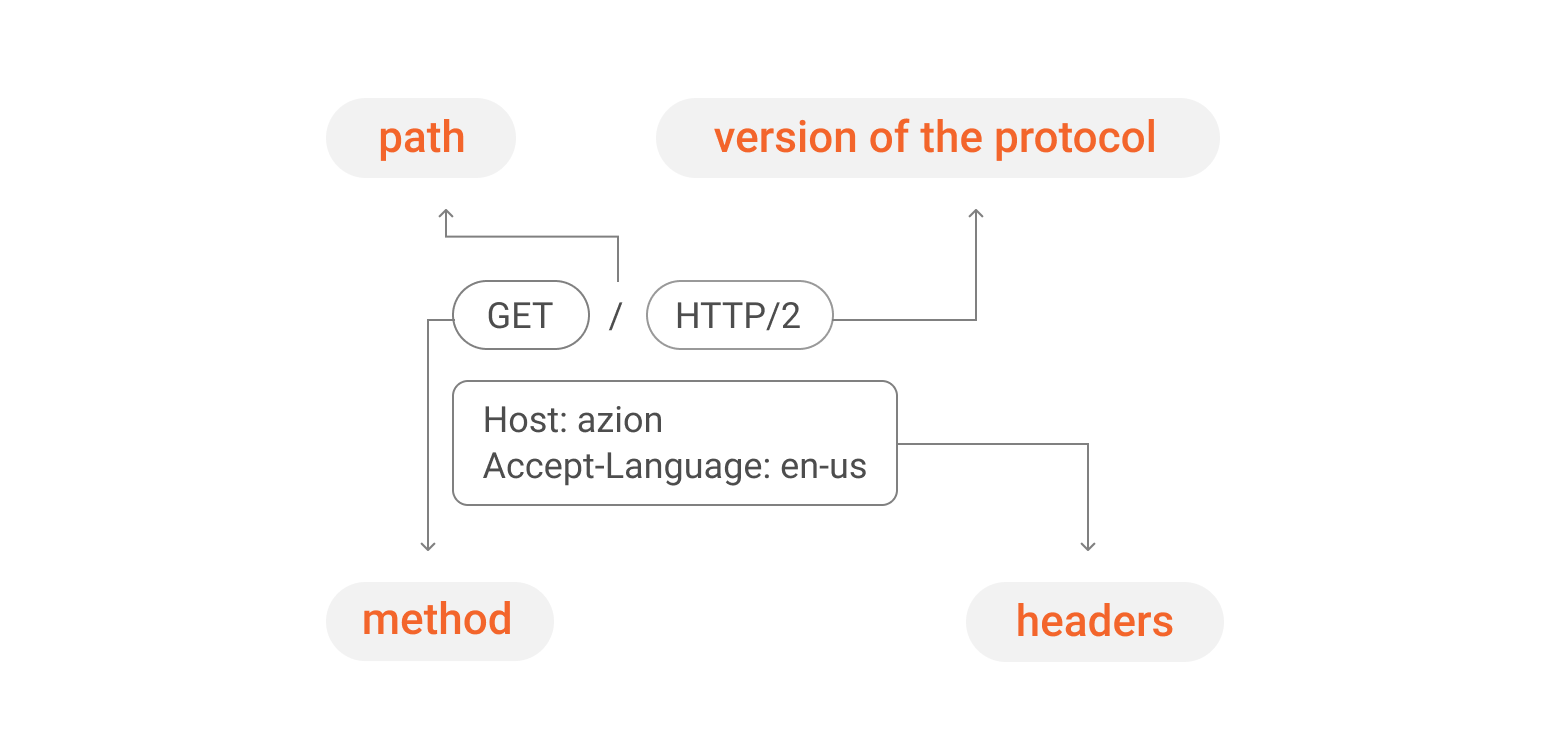

What Is a Request?

The request is what the client needs from the server. In that message, there is specific data, which describes what was requested. The main components of a request are described below.

- The method - indicates the action the customer wants to take, such as:

- GET - to obtain resources or retrieve data from the server; it’s the most common.

- POST - to send data to the server, such as submitting a form.

- HEAD - to resume the response line and headers.

- PUT - to send files to the server or do a full update of a resource.

- PATCH - to do a partial update of a resource.

- DELETE - to delete documents within the server.

- OPTIONS - to query which commands are available for a given user.

- TRACE - to debug requests, returning a document header.

2. The path - the URI (Uniform Resource Identifier) of the resource to be searched.

3. The HTTP version of the protocol.

4. The request headers - containing additional information for servers.

5. The request body - optional and necessary for some methods, such as POST, and contains the requested resource.

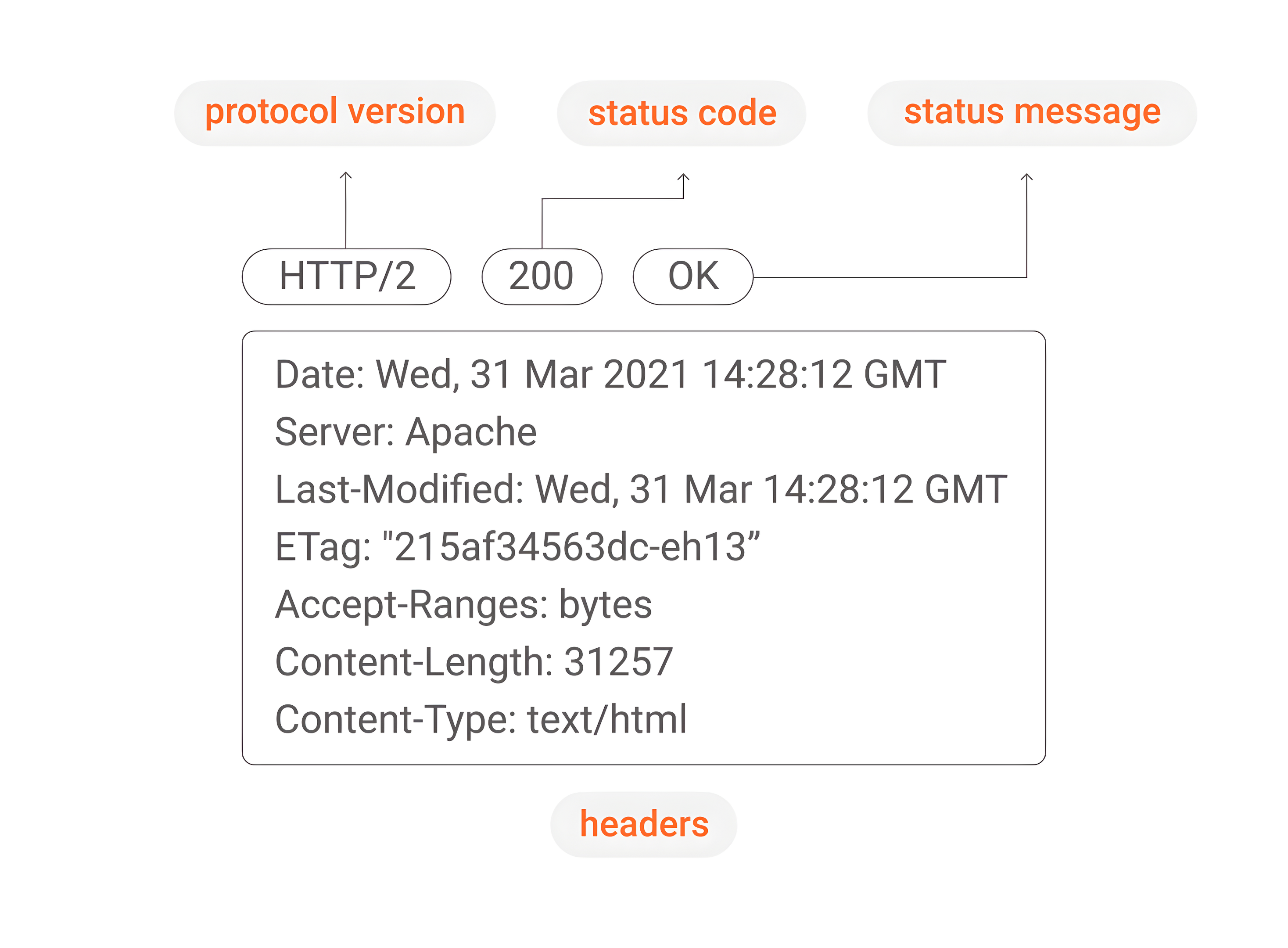

What Is a Response?

The response given by the server contains the information requested by the client or informs that there was an error in relation to what was requested. It contains the elements listed below.

- The response header - contains the protocol version, the request status code and the type of content that is included in the body.

- The status code - indicates whether the request was successful or not. The answer is given by specific codes, such as:

- 200 - the request was answered successfully.

- 301 - the request was permanently moved.

- 401 - the request wasn’t authorized by the server.

- 404 - the request wasn’t found by the server.

- 500 - internal server error.

- The response body - as in the request, is optional and contains data about the requested resource.

Another interesting aspect of the HTTP communication is the use of cache, which keeps copies of data that are frequently accessed. Basically, the cache speeds up the search and delivery of frequently used data and spares the use of resources on a server, improving the performance and speed of the process – but this is a topic for another article.

The Disadvantage of HTTP

You have seen that the HTTP protocol is the basis for any information exchange on the Internet, but, like everything else in this life, there is a catch: it’s not secure. Did you know that this is exactly why it’s the target of malicious actions? Among the cybercrimes that can affect the HTTP protocol, we can mention data interception during information transmission and DDoS attacks on layer 7, also known as HTTP flood attacks, which overload a server with HTTP requests. When the server is no longer able to respond to normal traffic, legitimate user requests will suffer denial of service.

Although all sites and applications are subject to cybercrime, the good news is that there are some ways to protect against these threats, like: Web Application Firewall, DDoS Protection, and Network Layer Protection.

Advanced Security Solutions

The Web Application Firewall (WAF) enhances the security of web applications by defending against a wide range of threats, from OWASP Top 10 vulnerabilities to sophisticated zero-day attacks. It safeguards the application layer (layer 7), where applications interact with network services, by acting as a protective barrier that applies a set of rules to filter and monitor traffic between the application and the Internet. In practical terms, WAF focuses on securing HTTP/S protocols by analyzing requests, detecting, and blocking malicious activities before they can impact infrastructure—all without compromising application performance.

The DDoS Protection solution offers multiple layers of defense against DDoS attacks, including those targeting layer 7, where the HTTP protocol operates. By leveraging a globally distributed network alongside specialized mitigation centers, it provides the intelligence and scalability required to neutralize even the most complex and large-scale attacks.

For even broader security coverage, Network Layer Protection establishes a programmable security perimeter at the network edge, controlling inbound and outbound traffic. This solution enables the ability to block threats, monitor suspicious behavior, and enforce penalties such as access limitations.

Adopting these mitigation strategies helps businesses stay resilient against emerging cyber threats, including increasingly frequent and large-scale attacks, targeted API exploitation, and evolving attack methodologies.

The Importance of HTTP

HTTP is a simple protocol, but more than that, it’s a striking feature that is also accessible, since it was designed to have messages that can be read and understood by any user. In addition, its stateless nature simplifies the performance of the server and makes it faster, since there is no need to store or clear data for the next requests. If a transaction is interrupted, no part of the system needs to be responsible for cleaning up the current state of the server. Another fundamental aspect is the fact that it’s extensible, which allows the insertion of new functionalities and, consequently, HTTP follows the needs and the evolution of the Internet in its mission to transmit the data that practically runs the world.

Metrics and how to measure HTTP performance & reliability

- Latency (end-to-end): time from request sent to response received.

- Measure with RUM, synthetic tests, or APM; separate DNS, connect, TLS, TTFB, download.

- TTFB (Time To First Byte): server + network responsiveness before body download.

- High TTFB often indicates backend, origin distance, or queueing.

- Status code rates:

- 5xx rate (server errors), 4xx rate (client/auth/validation), 429 rate (rate limiting).

- Cache hit ratio: % of requests served from cache at browser/CDN/edge.

- Low hit ratio often means bad cache headers or overly unique URLs.

- Throughput (RPS) and error budget:

- Track capacity under load; correlate error spikes with deployments.

- Connection metrics:

- TLS handshake time, retransmissions (esp. for mobile), HTTP/2 vs HTTP/3 adoption.

- Payload size:

- Large HTML/JSON/images increase download time; compress where appropriate.

Common mistakes (and fixes)

- **Mistake: Using HTTP (no TLS) for anything sensitive.

- **Fix: Default to HTTPS; redirect HTTP→HTTPS; enable HSTS where appropriate.

- **Mistake: Misusing methods (e.g., changing data with GET).

- **Fix: Use GET for safe retrieval; use POST/PUT/PATCH/DELETE for mutations.

- **Mistake: Cache headers that prevent caching or cause stale content.

- **Fix: Set Cache-Control intentionally; use immutable versioned assets; validate with ETag.

- **Mistake: Treating 4xx as “server problems.”

- **Fix: Segment metrics by status class; investigate 401/403 auth, 404 routing, 429 throttling.

- **Mistake: Assuming “stateless” means “no sessions.”

- **Fix: Add state via cookies/tokens; keep session storage explicit and secure.

- **Mistake: Ignoring intermediaries (CDNs/proxies) and debugging only at origin.

- **Fix: Log/trace request IDs end-to-end; verify headers at each hop.

Security: HTTP’s main disadvantage

**Plain HTTP is not encrypted, so traffic can be intercepted or modified in transit. **Decision rule: Use HTTPS for almost all modern web and API traffic and add application-layer protections for common Layer 7 attacks (e.g., bot abuse, injection, HTTP floods).

Common HTTP-layer threats include:

- Credential stuffing and brute force on login endpoints

- OWASP Top 10 attacks (injection, XSS, etc.)

- Layer 7 DDoS (HTTP floods) that overwhelm apps with legitimate-looking requests

How this applies in practice

If you run a website or API in production, HTTP decisions typically include:

-

Protocol choice: enable HTTP/2 and evaluate HTTP/3 for performance on mobile/unstable networks.

-

Caching strategy: decide what can be cached, for how long, and where (browser vs edge vs origin).

-

Authentication: choose cookies vs bearer tokens; enforce secure headers and TLS.

-

Protection: apply WAF rules, rate limiting, and DDoS mitigation for Layer 7 endpoints.

-

Observability: collect logs/metrics/traces tied to request IDs to debug latency and errors.

Mini FAQ

Is HTTP the same as HTTPS? No. HTTPS is HTTP over TLS, which encrypts the connection and authenticates the server.

Why is HTTP called stateless—how do logins work then? HTTP does not require server memory of prior requests; logins work by sending cookies or tokens on each request.

Which HTTP version should I use? Use HTTP/2 by default for broad compatibility; consider HTTP/3 when you need better performance on lossy networks and your stack supports it.

What do 301, 401, 404, and 500 mean? 301 = permanent redirect; 401 = unauthorized; 404 = not found; 500 = server error.

How do I speed up HTTP? Reduce TTFB, enable caching, compress payloads, use HTTP/2 or HTTP/3, and move content closer to users with edge/CDN infrastructure.

Glossary (quick reference)

- URL: address of a resource (scheme + host + path + optional query/fragment).

- URI: identifier for a resource (broader than URL).

- Method: action (GET/POST/PUT/PATCH/DELETE).

- Headers: request/response metadata.

- Status code: outcome signal (2xx success, 3xx redirect, 4xx client error, 5xx server error).

- Cache-Control / ETag: HTTP caching controls.

- OSI Layer 7: application layer where HTTP operates.

Summary

HTTP is the web’s standard protocol for requesting and delivering resources through a stateless request–response model, operating at Layer 7 and relying on TCP or QUIC for transport. In production, the key decisions are: use HTTPS, choose HTTP/2 or HTTP/3, design caching correctly, measure latency/TTFB and error rates, and protect endpoints with Layer 7 security controls.